The night before, Bob Dylan, backed by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, had played a concert at the Valby Hallen in Copenhagen, the 11th night of his Temples in Flames tour that began in Tel Aviv, and would end in London in mid-October.

At his concert in Rotterdam, two days earlier, he had asked me to come to Copenhagen and accompany him on the tour. He liked the body work I had done with him in Rotterdam when he’d said he wasn’t feeling good, and didn’t feel like playing. And he liked the conversation we were having – about his favorite guitarist, Michael Bloomfield, whom he knew I had been with until his tragic death six years earlier, and about whom I had come to ask Bob to help fund a documentary. But I think he liked me asking if he remembered being Shakespeare, more than anything.

We woke up in the penthouse hotel suite overlooking Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, followed by a knock on the door, and a young man rolling breakfast in like a scene change in a film. From the moment this adventure began, I had found myself swinging like a pendulum between ecstatic disbelief and simple, grateful acceptance of something inexplicably familiar. Mysteriously, I had an underlying feeling of coming home after being far away for a very long time.

As I opened my eyes, the pendulum swung and I could barely believe where I was: am I dreaming, waking up next to Bob Dylan? You think you know the basic plot of the story of your life until you find yourself unexpectedly in another story altogether, like accidentally walking into the wrong theater in the dark, in a multiplex cinema. A moment later, the pendulum swung back, slowly as the heartbeat of a blue whale, taking me back to the home base of dejà-vu.

The room reminded me of watching old Hollywood musicals on a Saturday morning, where a white satin gown and high curtains stand pure as marble pillars in a temple.

I went over to the window to see if the swans were on the lake, but the sun blazed like a spotlight so I kept them closed, so Bob wouldn’t be blasted by it, and the waking could be slow. Suddenly Theodore Roethke’s poem, The Waking, came to mind:

This shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

“That’s me,” I thought. “There’s a reason that I am here, but neither of us quite know what it is.”

In the low light morning, we spoke in looks and silences, savoring the quiet, and then, slowly, the coffee. It wasn't strange at all, this barely knowing each other, and waking up to feeling so familiar. It would seem strange if you were thinking logically. Thankfully, we weren’t. With Bob it was clear that feeling, not logic, was the spirit in charge. I remembered more of the poem:

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

It would take 24 hours on the road and on the sea to reach Helsinki for the next show. Victor called to remind us we had an early departure on the bus. I picked up the 4-page printed itinerary Bob had given me in Rotterdam, like the key to the kingdom. I could see the sequence of every city, venue, hotel and ferry, and not have to annoy anyone by asking when the boat leaves, or how many hours will we be on the bus today.

There would be a short afternoon ferry ride from Helsingør, just north of Copenhagen, over to Sweden. Then a 7-hour drive up to Stockholm. There, we would board the midnight ferry to Turku, Finland, sleeping on board and arriving late in the morning. From Turku it would be another two hours on the bus to Helsinki, for the concert that night.

It was almost noon when we were leaving the hotel in Copenhagen. In case Bob wanted some time alone I headed down to the bus on my own. I saw bags on the sidewalk next to the luggage compartment under the bus, and added mine, a shoulder bag and a garment bag which my mother had given me years earlier – not my style, but handy for keeping clothes from wrinkling. When Bob arrived, he saw it, raised his eyebrows and said,

"You brought that?"

It shook me, and the pendulum swung abruptly, darkening the moment like a cloud blocking the sun, reverie turning into doubt, afraid I'd disappointed him. But I caught myself, and thought, this isn’t fair. It’s so simple, basic: to bring a dress, put in the effort to look good, either you have to bring an iron, or a garment bag, because nothing looks good wrinkled. (I forgot that I could always ask the person in charge of wardrobe if I could use her iron.) Bob had never said a word about how long I'd be traveling with him, and I never asked. We both knew it would all depend on how it felt. I wanted to be prepared for anything. So yeah, that brown nylon garment bag was the epitome of uncool. Nothing rock and roll about it: no road scars, no big sexy metal zippers or backstage passes. It wasn't even black.

"Oh, man," he said, with a hint of an eye roll, but as we settled onto the bus I was happy to feel nothing had been damaged between us. Not even scratched. Why would it, over something so silly? But it showed me how vulnerable I felt. How would I steady myself?

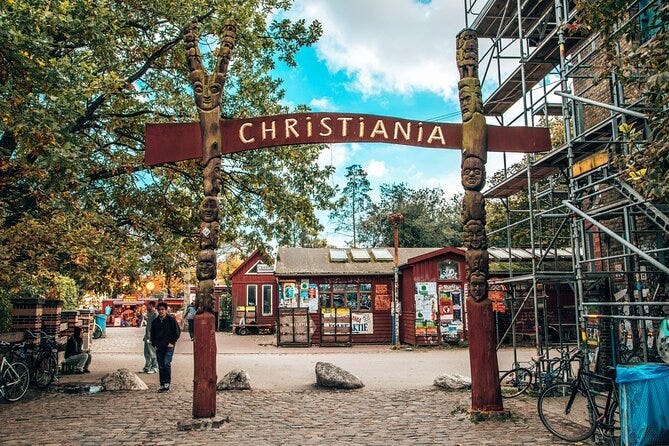

Before we left Copenhagen, Bob wanted to check out Freetown Christiania, the hippie community started in 1971 near the docks. It was a testament to the peaceful revolution of the psychedelic counterculture, determined to create their own community with their own laws, in the abandoned compound of army barracks and horse stables and surrounding land. It had been sitting empty for a few years, and was in serious disrepair, but they restored it, made living quarters in it, and painted it with bright designs, giant sunflowers, faces, mystical symbols, poetry and slogans. And it was still going strong, 16 years later.

Bob was inspired by the history of the place, how the people had managed to convince the government to respect their right to make their own laws for their community. Selling weed and hash was fine, for instance, but they knew hard drugs would bring the whole thing down, and tried – not always successfully – to keep them out.

"I'm thinking about making a movie about Christiania," Bob said.

"Really? What a great idea! I was there right after it opened, September, '71," I said. "It was wild and sweet, lots of artists, people re-inventing their reality."

"What were you doing there?"

"I was 17, backpacking alone around Europe. I wanted to find any relatives I might have in Copenhagen. I was in Tivoli watching the pantomime and at the end everyone was cheering and crying and bringing bouquets up to the stage for the Pierrot actor.

I asked the people next to me what was going on and they said it was his last show, and everyone had loved him since they were children. During the war, his shows had cheered people up and made them forget the horrors for an hour. They lived in Christiania and invited me back with them for the big farewell party they'd organized, and the actor came, too

.

"Alright. That's your name now: Christiania. I want you to be in the movie,” he said, quite seriously, but with a twinkle in his eye, watching me closely for my reaction. I laughed, but he didn’t. Apparently he meant it. “What else do you remember?"

"One of the rooms in this place – which had been the stables – was huge, and completely empty except for one thing: a giant bean bag sculpture made of pink painted canvas of a naked woman. She looked like the Primordial Mother Goddess, the Venus of Willendorf, Mother Earth herself. The moment I saw her from the doorway, I ran across the room and leapt high in the air, landing on her belly. Like a healing dream. Like I'd been looking for her all my life. I didn't have a hugging kind of mother. That idea of art as healing seemed like the spirit of the place. People in the place who saw me seemed to understand immediately, like that’s what they had made it for, like we all need to get a hug from the Great Mother now and then.

Then the party started. Everyone walking in with steaming fresh baked bread, pies, beer and wine and big bowls of food to share. When the actor arrived, we all cheered, many hugged him, some cried. It was a big moment.”

"Could you imagine actually living there? Could people still have some privacy?”

"Yeah, I did think about it. It felt so easy-going, like maybe everyone did tai chi, which I did, too. I liked the feeling of a big crazy family, loose, funny, all the things my family wasn’t. I loved how happy it seemed, the sunflowers blooming in the field, lots of projects going on, an outdoor stage for children’s theater, kind of chaotic, but full of hope. And it did seem like there were places to carve out your own quiet place in it.”

“So you’re Danish, huh?”

"On my dad’s side. In fact, his father had worked there, when it was a barracks and stables. They recruited him off the farm to join King Christian's bodyguard. They rode horses, wore big black fur hats, bright red coats, tight white pants. Probably all the girls wanted to marry them. But as soon as he got paid, he caught a boat for San Francisco. It was 1900. He never came back. Hardly anyone ever did."

Bob was looking out the window. “Okay, Christiania, looks like we’re here.”

I wished I hadn't rambled on so long, but he always seemed to be in the state of listening – to something inside or outside – and it was hard to know which. (I should have known better, having spent my childhood weekends in bars with my dad, hoping each pause in his story would be the end, so we could get out of the dark and into the sunlight. But he loved to tell stories and have the whole place under his spell, gesturing with his big Danish hands through the smoke, telling some San Francisco history he'd lived through, and there was no stopping him. He said it ran in our blood, we had a Danish ancestor who was a famous storyteller. I suppose it's true, as I was always made fun of for talking with my hands and not knowing when to stop.) When Bob had asked me to come with him, he'd said, “Nobody talks to me the way you do.” But more than once he let me know when it was too much.

It was a relief, though, when he said that out loud. The hardest thing about being on the tour with him was trying to guess what he wanted. Like Joan Baez sang in “Diamonds and Rust,” he was "so good at keeping things vague." It felt like he expected me to be able to read his mind and feel his feelings, and some of the time, I could. I shouldn't have to ask. So I tried to read his silent signals about whether he wanted my company or not at any moment. When I got it wrong and left him alone, and he had to wonder where I was, he let me know I'd let him down.

As we pulled up to Christiania, Bob was excited, a big smile on his face, curious to see what it was like. We got out and looked around a bit. Half the people on the street didn't see past his grey hoodie, but one by one people started recognizing him, and crowding around him. I felt very protective, but saw Victor and Jim Callahan, in charge of security, handling it like the pros they were. He didn't let it bother him, but after a few minutes he’d had enough and we climbed back on the bus. I couldn't tell if anything he'd seen had sharpened or dulled his interest in Christiania's history. I wondered how far his inspiration to make a movie would go. Of course, I knew he had it in him. I’d loved Renaldo and Clara.

Victor – who always rode up front, chatting and consulting with the driver about directions (it was a few years before GPS) and Jim – suggested stopping for lunch before going to the port, but Bob wasn’t interested. It was easy to see how tiring it was for him to be exposed to the public, and how he may not always have the energy for it, so we headed straight to the pier, with the blue September sky overhead, beckoning us onward.

I really enjoyed reading this. Thank you for continuing the story here. Just before I saw this come through I was listening to a part of an interview with Bob from 1977 about Renaldo & Clara — Bob asking the interviewer a couple of times how a specific part made him feel. Reading your words here you mention him being more into feeling than logic, which seemed to connect what I had just been listening to. (also him asking you what do you remember..).. Making a film.. and as reading I sensed you would mention Renaldo & Clara, and you did. The reason I got to listening this interview was a Shakespeare reference in something Bob possibly wrote.. I like how all this was. The timing. Connections. I don't have this all the time... But I recall last year when I read your words about Bob I had similar... I think maybe I told you!?..Either way, this is the part I had decided to post on here, before I read your words here..

https://substack.com/@nightlymoth/note/c-97292460

Best wishes,

nm

I just posted something on youtube -- The last Slow Train Coming (so far) .. I decided to post after seeing a Bob Dylan painting from last year -- Dusty Tracks. I somehow hadn't realised that he hadn't played that song since 1987. 20th September, 1987. Hanover, Germany. I thought of you and your first meeting with Bob, seeing that date .. I thought it must be around the same time. I just realised that must have been the night after you first met him? .. and then you met up with him again the night following this? https://youtu.be/s0WwjadHL1g?si=RsrG5xN5APBkR1Af